2021 Report & Data

Download: 2021 Full Report | Data Model | 2019-2021 Raw Data Files | 2021 Methodology Report

Translations (Abridged Report): Arabic | Chinese | French | Russian | Spanish

Overall Finding

Although many countries were able to quickly develop capacities to address COVID-19, all countries remain dangerously unprepared for meeting future epidemic and pandemic threats. A great opportunity exists, however, to make new capacities more durable to further long-term gains in preparedness.

-

Supporting Data

- The global average is 38.9 out of 100, with effectively no change since 2019, showing continued, severe weaknesses in global health security.

- Four of the six GHS Index categories have an average score below 40 out of 100, indicating the need for more concerted action in the prevention, detection and reporting, response, and health systems areas of capacity building.

- Since 2019, average scores in three of the six categories—prevention, response, and risk environment—saw a decrease, highlighting the lack of progress during a public health emergency.

- Out of 195 countries, of the 64 with publicly available national public health emergency response plans for specific diseases, 32 countries have evidence of COVID-19- specific plans.

- Forty-nine countries have a national system in place to provide support at the subnational level to conduct contact tracing in the event of a public health emergency, and 37 of those countries had created it for their response to COVID-19.

Additional Findings

-

Most countries, including high-income nations, have not made dedicated financial investments in strengthening epidemic or pandemic preparedness.

- The overall average score for national-level financing is 35.2 out of 100.

- 90 countries have not fulfilled their full commitment to contribute to the WHO; of those, 14 are high-income countries.

- 66 countries have not identified special emergency public financing mechanisms and funds that the country can access in the face of a public health emergency; of those, 32 are high-income countries.

- 155 countries have not allocated nonemergency national funds within the past three years to improve their capacity to address epidemic threats; among those, only two low-income countries have evidence of allocated funds.

- The average score for national financing for epidemic preparedness is 21 out of 100; low-income countries have an average score of 7 out of 100.

- Financing for emergency response has a global average score of 66. High-income countries have the lowest average score of 46; low-income countries have the highest average, with 93.

- Only four countries (Eritrea, Indonesia, Liberia, and Timor-Leste) have a JEE or NAPHS that describes specific funding from the national budget to address previously identified gaps.

- High-income and upper-middle-income countries receive the lowest scores for financing when reviewed under the JEE and OIE Performance of Veterinary Services (PVS) Pathway assessments and related to financing for emergency response.

- The average score for financing under the JEE and PVS report is 1 out of 100; this score reflects the provisions for funding IHR implementation through the national budget or other mechanisms.

-

Most countries saw little or no improvement in maintaining a robust, capable, and accessible health system for outbreak detection and response.

- The overall average score for health systems remains low across all countries, at 31.5 out of 100.

- Sixty-nine countries have insufficient health capacity in clinics, hospitals, and community centers.

- For key measures on health capacity in clinics, hospitals, and community centers, scores remain unchanged and low. Those measures include available human resources, such as physicians, nurses, and midwives; strategies for growing the healthcare workforce; and number of hospital beds, scoring an average 30 out of 100, with low- and low-middle-income countries showing averages below 20 out of 100.

- The global data on available human resources and hospital beds are not routinely updated, creating a dated understanding of baseline capacity.

- Only 49 countries have published an updated health workforce strategy that identifies fields with an insufficient workforce and provides strategies for addressing those shortcomings.

- Deficiencies in healthcare access exist across all income levels. Although the United States may rank first overall for the health systems category, it is ranked 183 globally on measures of healthcare access and ranked 55 out of 59 among high-income countries on measures of out-of-pocket health expenditures. The United States was one of just five high-income countries that does not provide paid sick leave.

- In the WHO Region of the Americas, Cuba ranks highest in physician density (842.2 doctors per 100,000 people), whereas the highest-ranking country in the African Region, Mauritius, reports only 253.3 doctors per 100,000 people.

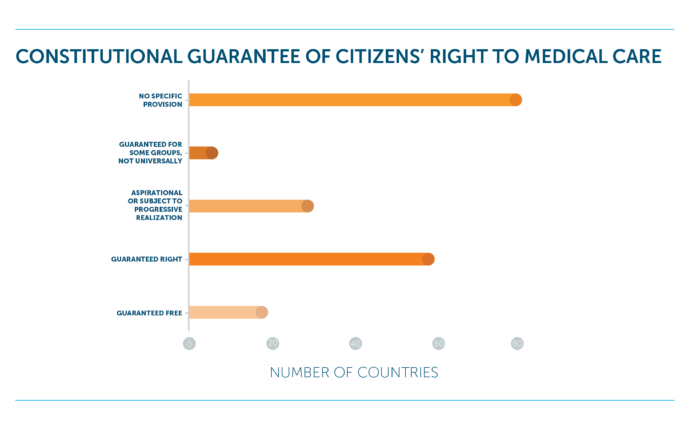

- 40% of countries do not have a constitution that explicitly guarantees citizens’ right to medical care, a statistic that does not vary greatly even across income groups.

- High-income countries scored the lowest in terms of constitutional guarantees of medical care. North American countries scored the lowest of all regions, with a striking score of 0.0, whereas the Middle East and Northern Africa regions12 scored the highest in this indicator, at 52.5.

-

Political and security risks have increased in nearly all countries, and those with the fewest resources have the highest risk and greatest preparedness gaps.

- The average country score for public confidence in government is 44.4 out of 100, with El Salvador, Mexico, and Tajikistan showing the largest increases in scores.

- 114 countries demonstrate a moderate to very high threat of international disputes or tensions that would have a negative effect on daily operations—such as those related to public services, governing, and civil society—and 24 high-income countries score below the global average.

- Only 16 countries score in the top tier for government effectiveness, with 129 countries scoring below 50 out of 100. This indicator includes measures such as policy formation, quality of bureaucracy, excessive bureaucracy, cronyism, corruption, accountability of public officials, and human rights.

- No low-income countries score above 50 out of 100 for the orderly transfer of power, revealing little to no clear, established, accepted constitutional mechanisms for transfer from one government to another.

- An increased number of countries show greater risk of social unrest, with 78 showing a high to very high risk of elements that could cause considerable disruption or seriously challenge government control of the country. The social unrest subindicator was the largest drop across all political and security risk subindicators.

- 34% of countries show evidence of a moderate to very high threat of terrorist attacks with a frequency or severity that causes substantial disruption.

- Low-income countries saw the most significant increase in risk with respect to armed conflict and government territorial control, with an average score of 37 out of 100, as opposed to high-income countries, which had an average score of 94.9 and 98.3, respectively, indicating significantly lower risk.

- 65% of all countries scored below the global average for political risks related to vested interests and cronyism.

- Socioeconomic resiliency decreased across countries in all income levels except in high-income countries.

- The average score for trust in medical and health advice from the government is 52.3. The average country score for public trustin medical and health advice from medical providers is slightly higher, at 68.5 out of 100.

-

Countries are continuing to neglect the preparedness needs of vulnerable populations, exacerbating the impact of health security emergencies.

- Global progress toward closing gaps between vulnerable and non-vulnerable groups has slowed, decreased, or shown no change since the 2019 GHS Index.

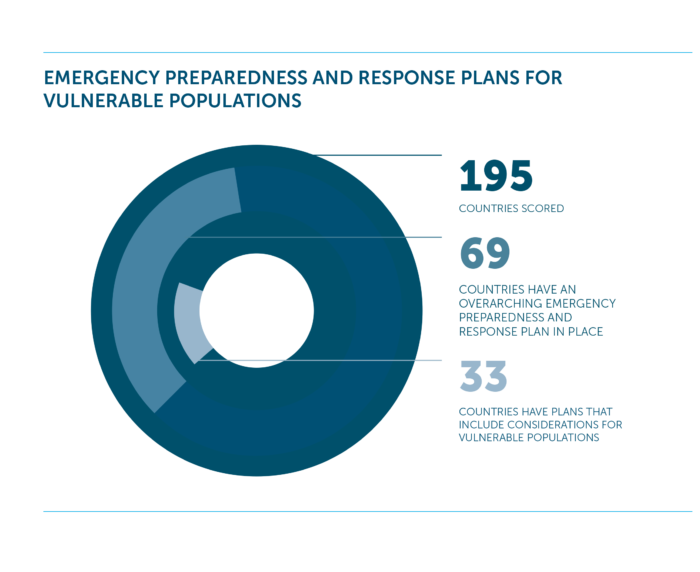

- Very few countries have planning or legislation to address vulnerable populations in public health preparedness; 69 countries have an overarching plan in place, but only 33 countries include considerations for vulnerable populations in their plans.

- Average scores for gender equality, including reproductive health, empowerment, and economic status, have decreased since 2019, averaging 58.4 out of 100.

- 76% of countries do not outline how risk communication messages will reach populations and sectors with different communication needs related to language, location, and media reach.

- Although most countries include social and financial assurances of paid medical leave, with 93% of countries having paid medical leave, this trend notably does not include nine upper-middle- and high-income countries (Cook Islands, Marshall Islands, Nauru, Niue, Palau, South Korea, Tonga, Tuvalu, and the United States).

- 81% of countries do not provide wraparound services, such as economic and medical attention, to enable infected people and their contacts to self-isolate or quarantine as recommended.

-

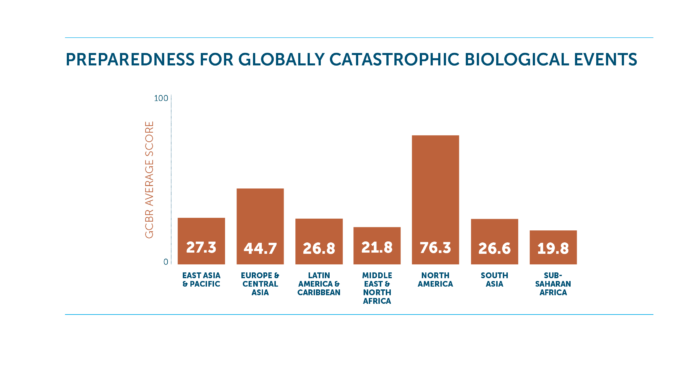

Countries are not prepared to prevent globally catastrophic biological events that could cause damage on a larger scale than COVID-19.

- 65% of countries do not have an overarching national public health emergency response plan for diseases with epidemic or pandemic potential.

- 178 countries score below 50 out of 100 points for biosecurity measures, including whole-of-government biosecurity systems, biosecurity training and practices, personnel vetting and regulating access to sensitive locations, secure and safe transport of infectious substances, and cross-border transfer and screening.

- 94% of countries have no national-level oversight measures for dual-use research, which includes national laws or regulation on oversight, an agency responsible for the oversight, or evidence of a national assessment of dual-use research.

- 144 countries have no national and subnational reporting surveillance system that includes ongoing or real-time laboratory data.

- 73% of countries do not have the ability to provide expedited approval for human medical countermeasures, such as vaccines and antiviral drugs, during a public health emergency.

- 152 countries have not demonstrated linkages or established procedures or guidance between public health and national security authorities for responding to a biological event.

Categories

![]()

The GHS Index includes six categories, each covering a range of indicators and questions. Results at this level provide insights into the overall finding:

-

Prevention

Definition: Prevention of the emergence or release of pathogens, including those constituting an extraordinary public health risk in keeping with the internationally recognized definition of a Public Health Emergency of International Concern. Indicators in this category assess antimicrobial resistance (AMR), zoonotic disease, biosecurity, biosafety, dual-use research and culture of responsible science, and immunization.

2021 Findings: The global average for the prevention of the emergence or release of pathogens is 28.4 out of 100, making it the lowest-scoring category within the GHS Index. One hundred thirteen countries show little to no attention to zoonotic diseases within national planning, surveillance, or reporting for diseases—such as those caused by coronaviruses—that are transmitted from animals to humans.

-

Detection and Reporting

Definition: Early detection and reporting for epidemics of potential international concern, which can spread beyond national or regional borders. Indicators in this category assess laboratory systems strength and quality, laboratory supply chains, real-time surveillance and reporting, surveillance data accessibility and transparency, case-based investigation, and epidemiology workforce.

2021 Findings: This category shows major gaps in the strength and quality of laboratory systems, laboratory supply chain, real-time surveillance, and reporting capacities for epidemics of potential international concern. Only three countries (Australia, Thailand, and the United States) score in the top tier in the category of early detection and reporting of epidemics of potential international concern. Only 37% of countries have made a public commitment to share surveillance data, and only five (Brunei, Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, and Singapore) made commitments to share data specifically for COVID-19.

-

Rapid Response

Definition: Rapid response to and mitigation of the spread of an epidemic. Indicators in this category assess emergency preparedness and response planning, exercising response plans, emergency response operation, linking public health and security authorities, risk communication, access to communications infrastructure, and trade and travel restrictions.

2021 Findings: No countries scored in the top tier for this category, with 58% of countries scoring below average for rapid response to and mitigation of the spread of an epidemic. Only 69 countries have an overarching national public health emergency response plan in place that addresses planning for multiple communicable diseases with epidemic and pandemic potential. Although those numbers indicate serious gaps in exercising response plans, risk communication, and linking public health with health security authorities, COVID-19 has produced some new, evolving capacity in the rapid response and mitigation of a novel virus, such as non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPI) planning.

-

Health Systems

Definition: Sufficient and robust health system to treat the sick and protect health workers. Indicators in this category assess health capacity in clinics, hospitals, and community care centers; supply chain for health system and healthcare workers; medical countermeasures and personnel deployment; healthcare access; communications with healthcare workers during a public health emergency; infection control practices, and capacity to test and approve new countermeasures.

2021 Findings: The average score in the health system category is 31.5 out of 100, with 73 countries scoring in the bottom tier. Sixty-nine countries have insufficient capacity at health clinics, hospitals, and community centers. Ninety-one percent of countries do not have a plan, program, or guidelines in place for dispensing medical countermeasures, such as vaccines and antiviral drugs, for national use during a public health emergency. Altogether, the health systems category shows little progress since 2019 and identifies serious gaps in capacity in national-level medical workforce, facilities, and healthcare access.

-

Commitments to Improving National Capacity, Financing, and Global Norms

Definition: Commitments to improving national capacity, financing plans to address gaps, and adhering to global norms. Indicators in this category assess IHR reporting compliance and disaster risk reduction; cross-border agreements on public animal health and emergency response; international commitments; completion and publication of WHO Joint External Evaluation (JEE) and the World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE) Performance of Veterinary Services (PVS) Pathway assessments; financing; and commitment to sharing of genetic and biological data and specimens.

2021 Findings: Twenty-three countries—19 of which are high- or upper-middle-income countries—have not submitted their International Health Regulations reports to the World Health Organization (WHO), and only four countries have identified funding in their national budgets to address gaps identified in their WHO Joint External Evaluation (JEE). The 2021 GHS Index shows a lack of progress toward enhanced global coordination and lagging commitment to international norms, which are important for accountability and necessary for collective action in addressing the most challenging aspects of health security. For instance, in the past three years, only 50% of countries have submitted Confidence-Building Measures to the Biological Toxins and Weapons Convention.

-

Risk Environment

Definition: Overall risk environment and country vulnerability to biological threats. Indicators in this category assess political and security risks; socio-economic resilience; infrastructure adequacy; environmental risks; and public health vulnerabilities that may affect the ability of a country to prevent, detect, or respond to an epidemic or pandemic and increase the likelihood that disease outbreaks will spill across national borders.

2021 Findings: As seen with COVID-19, national risk environment factors, such as orderly transfer of power, social unrest, international tensions, and trust in medical and health advice from the government, can have an outsized impact on a country’s response to a public health threat. One hundred fourteen countries demonstrate a moderate to very high threat of international disputes or tensions that would have a negative effect on daily operations—including public services, governing, and civil society—with 24 high-income countries scoring below the global average.

Recommendations

Given what has been learned from the COVID-19 pandemic thus far, the following recommended actions for countries, international organizations, the private sector, and philanthropies and funders would strengthen the global and national preparedness for the next pandemic.

-

Countries

- Prioritize the building and maintaining of health security capacities in national budgets. Those capacities are not just beneficial for health security emergencies; they are important for responding to routine health threats and can provide important benefits to countries’ overall health and development.

- Conduct assessments, using findings from the 2021 GHS Index, to identify their risk factors and capacity gaps, and develop a plan to address them.

- Develop, cost, and make financial arrangements to support a National Action Plan for Health Security if they have completed Joint External Evaluations.

- Undertake a JEE to better understand their gaps if they have not done so already. Data from the 2021 GHS Index may be used to update JEE data and supplement it with additional data regarding health systems and risk factors.

- Be more transparent with their capacities and risk factors. National decision makers need readily available information about their country’s plans and other capacities, and increased transparency is essential for global prevention, detection, and response to epidemics and pandemics.

- Conduct comprehensive after-action COVID-19 pandemic reports so that they can learn from this crisis and ensure that capacities developed during the pandemic are expanded and sustained for future public health emergencies.

-

International organizations (such as the UN, WHO, and World Bank)

- Use the findings of the 2021 GHS Index to identify countries that may benefit most from additional support to improve their readiness for future disease emergencies, prioritizing assistance to countries with higher political and socioeconomic risk factors.

- Support countries in addressing the urgent global need to strengthen health systems as part of countries’ public health capacity-building efforts.

- Work with countries to make available more data, especially standardized data, that can be used to assess the strength of health systems, particularly with respect to their preparedness for infectious disease emergencies.

- Use data from the 2021 GHS Index to supplement their efforts to monitor ongoing and future disease emergencies to identify where rapid deployment of international assistance may help to mitigate the impact of events and prevent cross-border spillover.

- Support the formation of a dedicated international normative body to promote the early identification and reduction of globally catastrophic biological risks.

- Work to improve coordination among national and global actors to address highconsequence biological events, including deliberate attacks. Specifically, the Office of the UN Secretary-General should work in concert with the WHO, the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, and the UN Office for Disarmament Affairs to designate a permanent facilitator or unit for high-consequence biological events and call a heads-of-state-level summit on biological threats that is focused on creating sustainable health security financing and new international emergency response capabilities.

-

Private sector

- Use the 2021 GHS Index to partner with governments to help address gaps in country preparedness and to assess likely vulnerabilities in countries where they operate. Companies and other private organizations should use these findings to encourage governments to make improvements.

- Identify and support private-sector resources, plans, and programs that can augment government capacities, especially in countries with few developed capacities.

- Increase their sustainable development and health security portfolios in research, development, and capacity building, using the 2021 GHS Index to identify priority areas aimed at preventing epidemics and pandemics from causing catastrophic damage on a global scale.

-

Philanthropies

- Create new financing mechanisms, such as a global health security matching fund, and expand availability of World Bank International Development Association allocations to allow for investments to fill epidemic and pandemic preparedness gaps for countries in need.

- Use the 2021 GHS Index to prioritize resources. Countries with low scores related to risk environment—including political and security, socioeconomic, infrastructure, environmental, and public health risks— should be identified as priorities for capacity development and should receive prompt international assistance when infectious disease emergencies occur within their borders.

- Advocate to country governments to make available national resources to support preparedness and capacity development.

Methodology

The 2021 GHS Index includes research for the same 195 countries included in the inaugural edition. Country research was conducted from August 2020 through June 2021. Economist Impact conducted the research for this Index through a combination of qualitative assessments of publicly available country information and examinations of existing quantitative data sets. Given the complex nature of global health security, Economist Impact developed a multidimensional analytical framework, commonly known as a benchmarking index, in order to create an objective, country-level assessment tool. A multidimensional framework is a useful way of measuring performance that cannot be directly observed, such as a country’s economic competitiveness or, in this case, a country’s health security conditions. Download the full Methodology report here.

Methodology FAQs

-

What is the best way to use the GHS Index Model?

The indicators in the 2021 Global Health Security Index are embedded in an interactive model (available as an Excel workbook at the top of this page) that offers a wide range of analytical tools, thereby allowing a deeper investigation into measures of global health security. For example, users can filter countries by region, population, or income level, or directly compare any two countries. The model also includes data from the 2019 Global Health Security Index, allowing users to view country performance for both GHS Index years (note: data for 2019 have been re-scored to accommodate changes made to the GHS Index in 2021). A user can also examine correlations between indicators. Individual country profiles, which include the consulted sources and scoring justifications, are also included in the 2021 Global Health Security Index model, thus permitting a deeper dive into the health security conditions in each country.

The GHS Index model is designed to allow the users flexibility in how they analyze the data. Although the GHS Index model relies on a neutral weighting scheme for analysis, the weights assigned to each indicator can be changed by the user to reflect different assumptions about the importance of categories and indicators.

Finally, the model allows the final scores to be benchmarked against external factors that may potentially influence global health security, such as gross domestic product (GDP) per capita, the United Nations Development Programme’s (UNDP) Human Development Index, and many other relevant factors. The background indicators also include two COVID-19-specific metrics collected by the Economist Impact team: assessing if the country has made publicly available de-identified COVID-19 health surveillance data and contact tracing data.

-

What are the changes to the 2021 GHS Index?

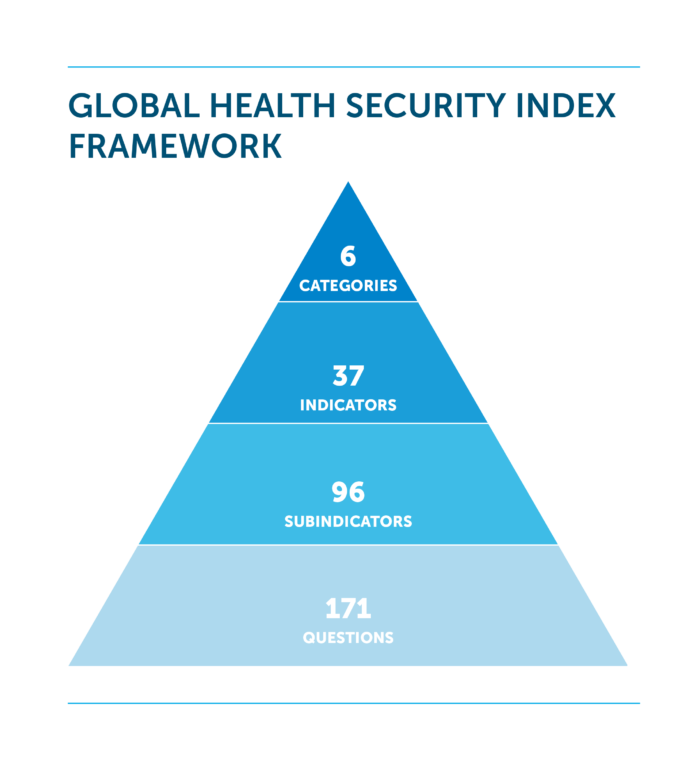

The 2021 GHS Index includes several indicators that have been revised or added into the framework. This GHS Index includes a total of 171 individual metrics (or questions), compared with 140 in 2019. The 2021 GHS Index includes new and revised questions on zoonotic disease spillover events, scaling testing capabilities for known and novel pathogens, financing, risk communications and misinformation, disinformation and rumors, among others. For a full overview of the new and revised questions, see the section “Select New and Revised Indicators” on page 25 of the Methodology Report.

-

What are the scoring criteria and categories?

The 2021 Global Health Security Index consists of 171 questions grouped into 37 indicators across six overarching categories. The Index includes research for 195 countries that compose the States Parties to the International Health Regulations (IHR [2005]).

The overall score (0–100) for each country is a weighted sum of the six categories. Each category is scored on a scale of 0 to 100, in which 100 represents the most favorable health security conditions and 0 represents the least favorable conditions. A score of 100 does not indicate that a country has perfect national health security conditions; likewise, a score of 0 does not mean that a country has no capacity. Instead, the scores of 100 and 0 represent the highest or lowest possible score, respectively, as measured by the Global Health Security Index criteria. Each category is normalized based on the sums of its underlying indicators and sub-indicators, and an identical weight is then applied. The default weights used in the ranking are based on neutral (or identical) weights. The weights in the model, however, are dynamic and can be changed by users.